The academic year 2015-16 is drawing closer to an end, and it’s been another great year for the Faculty. We thought it would be nice to have a reminder of some of the research that has come out of the Faculty this year so far. After all, what better year is there to do it than 2016? – When Manchester is named European City of Science. From all the positive research outcomes of the Faculty this year, it’s certain that this has helped Manchester live up to this name!

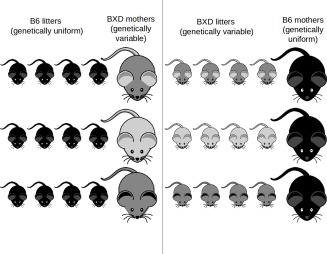

2016 started off with a paper published by FLS scientists which showed that there are genetic variants in offspring that can affect the quality of maternal behaviour. The trials for this study consisted of mice families with genetically variable mothers and genetically uniform offspring, and vice versa.

Dr Reinmar Hager, the senior author on the paper, told us how this research is unique:

“The aim was to identify genes that are expressed in offspring but influence the way mothers behave. Normally you try to identify genes that influence how you, and not others, behave. These genes act as indirect genetic effects. Previous research has shown that offspring can manipulate their parents’ behaviour, however, here we identify for the first particular genes with such effects.”

Photo: Locke et al (2015). ‘Genetic studies of body mass index yield new insights for obesity biology’. Nature, 518 (7538), 197-206.

It was found that variation in offspring genotype on chromosome 7 and chromosome 5 affects maternal behaviour, which in turn influences offspring development and fitness. It was also observed that offspring growth during the second week is affected by a locus on maternal chromosome, where the B6 allele increases the trait value – so individuals with the maternal phenotype B6 are genetically predisposed to give better quality care. Conversely however, genetic variation among mothers was found to influence offspring development independent of offspring genotype.

David Ashbrook from FLS was also involved in the research. He commented on the significance of these findings and their implications for the future:

“We identified genes which can now be studied in more detail, and shown that specific genotypes may be co-adapted to benefit both parties, e.g. genotypes which predispose to mothers who provide more care also predispose to offspring who beg less. We also demonstrate a method to investigate the genetic effects of social environment, which can now be used to examine adult phenotypes and associated reproductive success.”

Research of this kind is always interesting and useful to us as it can be applied to all social species, including humans. Identifying parent-offspring interactions is the first step in being able to understand the pathways involved with these, and how they are modified by our environment (social and physical).

Leading on from the idea of how the environment can influence our lives, a study involving FLS Professor Andrew Loudon was published later on in the month, showing the importance of having a circadian body clock that matches the rotational speed of the Earth. Scientists within our faculty are well recognised and respected as valuable experts in their research areas. For example, it is clear that the research conducted by Professor Andrew Loundon during his time in the Faculty of Life Sciences at The University of Manchester, has meant that he has become a reputable source to comment on other research in the same field. This is seen in a recent BBC article about making flu vaccinations more effective by administering them in the morning. Here, researchers from The University of Manchester, Prof Loudon one of them, were asked to comment on the idea of using the body clock to make healthcare procedures more successful due to it being done at a most appropriate time for the body’s natural rhythm. So not only do we do great research in the Faculty of Life Sciences, but we are an authority on what makes other research great too!

Similarly, this was also seen in in the discussion of CRISPR, a new gene editing technology that can explore organisms at an unprecedented scale of precision. CRISPR has taken the world of biological sciences by storm, and has enormous application in holding the capability to modify the human germline. Although this discovery was not directly from the Faculty, Matthew Cobb, Professor of Zoology at the University of Manchester, was asked by the BBC to host a show on radio 4 to educate the public about the technology, and the implications and ethical issues it raises for the future. Again, examples like this just demonstrate how other well respected and popular sources value and trust the expertise of scientists in our Faculty!

Other great research from the faculty in January includes:

From early this year, the ZIKA outbreak spread through the Americas and the Pacific – and with it brought the panic associated with the virus and a need for prevention. Scientists at The University of Manchester responded to this by stating that a vaccine is to be developed here. So not only has this year been a great year in terms of research outcomes, but also research prospects! This is just one example of how scientists in the Faculty of Life Sciences are committed to helping people. This dedication to science is something that we as a faculty are very proud of at the University of Manchester, as it can have a hugely positive impact on people’s lives.

Another topic in science that has an impact on the way we live is climate change. A major challenge currently facing the world is how to mitigate this. Scientists have suggested many ways of dealing with climate change, but one that has been widely discussed is increasing the amount of carbon sequestered, or stored, in soil. The reasoning behind this is that soil is one of the world’s largest pools of carbon, so by increasing its size further, we should be able to draw down the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, thereby mitigating climate change.

A study involving Professor Richard Bardgett from the Faculty of Life Sciences consisted of sampling soils across the UK. It was found that over 2 billion tons of carbon is stored deep under the UK’s grasslands, which cover around a third of the UK land surface. This represents a huge amount of carbon that is helping to curb climate change. It was also found that 60% of this carbon is deep in the soil, hidden from past national carbon inventories. Another surprising finding was that carbon stored in grasslands, is sensitive to the way land has been farmed, and that decades of intensive grassland farming, involving high rates of fertilizer use and livestock grazing, have caused valuable soil carbon stocks to decline- the largest soil carbon stocks beneath grasslands had been farmed at intermediate levels of intensity, receiving less fertilizer and with fewer grazing animals. Carbon stocks were about 10% higher in these grasslands than in the more intensively managed grasslands.

Professor Richard Bardgett commented on these findings:

“These findings are important for two reasons. First, they show that much more carbon is stored in grasslands that previously thought, and second, they suggest that the amount of carbon in our grasslands could be increased by managing them in a less intensive way. Not only could this help in meeting our future global carbon targets, but also it could bring benefits for biodiversity conservation”

Other great research from the faculty in February includes:

It seems like 2016 has also brought with it the rise of digital technology in scientific research! During a visit from Life Sciences Minister George Freeman, a new home to the heath eResearch centre was opened at The University of Manchester, making us a hub for some of the world’s best digital and health research in the North of England! This is supported by a current experiment going on in the Faculty. With hay fever season quickly approaching, scientists from The University of Manchester are inviting people to get involved with one of the biggest experiments they have ever conducted to help understand why the frequency of allergies is increasing.

Currently 1 in 4 people have an allergy, a ratio that was not as high in previous years and is still on the rise – however the exact reason for this increase is currently unknown. A team of scientists, including some from The University of Manchester’s Faculty of Life Sciences, have launched an app called #BritainBreathing. This aims to achieve a better understanding of seasonal allergies by tracking how symptoms change over time and learn about your allergy triggers. Then, by teaming the data from #BritainBreathing with other sources of publicly available weather and pollution data, it will enable us to understand the patterns and causes of seasonal allergies.

One of the key traits of this experiment is science designed with citizens as partners, meaning that it is a collaboration between the scientists developing the app and allergy sufferers. Dr Sheena Cruickshank, Senior Lecturer in Immunology commented on this aspect of the project:

“We have involved the public from the outset with this project in order to not only consult about it but also to co-design the features of the app to ensure it is useful to the allergy community”

Dr Lamiece Hassan from the Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, is also involved with the project. She said:

“I don’t [have an allergy] myself yet, I say that because allergies are on the rise. Based on current projections, in 10 years over half of us will have an allergy. Digital technology is part of our everyday lives now and that brings huge opportunities for gathering data on a mass-scale for researchers like me.“

Other great research from the faculty in March includes:

-

HIV treatment could be used to help treat skin cancers

-

Groundbreaking text mining project highlights ‘gender gap’ in scientific research

In more recent FLS news, researchers have used a technique developed by Dr Michael Buckley from the Faculty of Life Sciences, called Zooarchaelogy by Mass Spectometry (ZooMS), to identify human traces from a Neanderthal bone in fragments located in Russia. Dr Buckley developed the method during his PhD, when he realised how difficult it is to identify between fragmentary animal bones. ZooMS works by fingerprinting collagen, an abundant protein in bone that survives for millions of years. This is done by extracting collagen into solution and using an enzyme to cut at particular amino acids, which then produces a set of protein fragments that are specific to particular animals. These are then analysed using a mass spectrometer to measure the sizes of the fragments.

Dr Buckley from the Faculty of Life Sciences told us about how ZooMS can be used:

“My recent developments at Manchester have been to upscale the methodology to make it work with thousands or even tens of thousands of samples, a very useful development whether hunting for human remains like a needle in a haystack, or evaluating palaeobiodiversity through time”

He continued to tell us about his involvement in the study:

“When I was screening through the batch of hundreds of samples and I spotted the hominin signature I was incredibly excited, as it was the first time that my method had been used to find such ancient human remains, and I am confident that it won’t be the last time.

“This finding continues to add to our knowledge of Neanderthal evolution, and potentially to our own interactions with them. As a method it could really revolutionize our picture of human evolution through the practical aspect of helping find much more material to obtain further genetic information from, such as ancient DNA.”

Well what an impressive year for the Faculty so far – and it’s only May! Aside from this, a number of members in the faculty have been rewarded for their research efforts, which recognises just how important and well-recognised the research conducted here is. Faculty experts continue to inspire us by the quality of research at The University of Manchester, making us proud to be a part of the Faculty of Life Sciences.

For recent updates in life sciences news, please visit: https://lsmanchesterblog.wordpress.com/

Reblogged this on Faculty of Life Sciences, UoM.

[…] via FLS research 2016 — Manchester Life Scientists […]